To be called upon to serve is, by right, an action that should be regarded with the highest esteem of honor. For whatever reasons that might come to motivate one to forsake the life of comforts for the cramped, impersonal, life in the barracks, there should be some level of respect. It is often easy as a nation of such wealth and comfort, to forget how different our lives can be. It could be all too easy to place oneself on a pedestal and look down on the choices of others, to condemn a war, or even to simply think lightly of the lives lead by our troops stationed around the globe. In regard to the past decade and a half of America’s global diplomatic thrust, and its effect on the general population, the jury is out. One can, in the same breath, recognize the publicity failings of the United States’ dealings with the rest of the world in the era of war on terror, and be so moved away from any vocal condemnation of the recent wars, by the acts of valor, constancy and discipline shown by members of the armed forces in situations that would reduce most to tremulous shaking.

The debate on the war, the military and America’s place in the world set aside, the lives’ of those who choose to answer the call to serve their country, are by and far a different breed from the world that is seen on the silver screen, or talked of in the comfort of one’s home, or even relayed with “accuracy” through the news stations. Life in the military is an odd place, a purgatorial waiting in the best of times, in the worst of times a frantic struggle to channel one’s adrenaline yet maintain such clarity and adherence to one’s training; it is, perhaps, best considered as an alternate reality world from the one seen through the jaded eyes of a civilian. Everything done in the civilian world is done differently. The news is handled in a strange way. Even the Military Police (MPs) struggle to fit in when transferring over to a similar police career in a normal, non-military setting.

Last November, a training accident at the Marine’s Camp Pendleton Zulu Impact Area (an Explosive Ordinance Disposal training site on the military base) tragically killed four Marines. These men had dedicated their lives to their country. Their families suffered the losses, grieving, and calamity of such a loss. Then something happened. Something strange happened. The story barely broke the news. A quiet blurb might have occurred here or there; perhaps an official statement from the Department of the Marines, but on the whole, this story was forgotten behind concerns over what Miley Cyrus had done with her body last week or who would win the next football game, or what deals might come up in the Black Friday sales. Perhaps one who knew a friend or a relative stationed at Camp Pendleton might have heard the news, but on the whole, this story went unmentioned. It is truly difficult to understand the disconnect between our nation’s military, our very own sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, our very own family members and friends, and the lives we live.

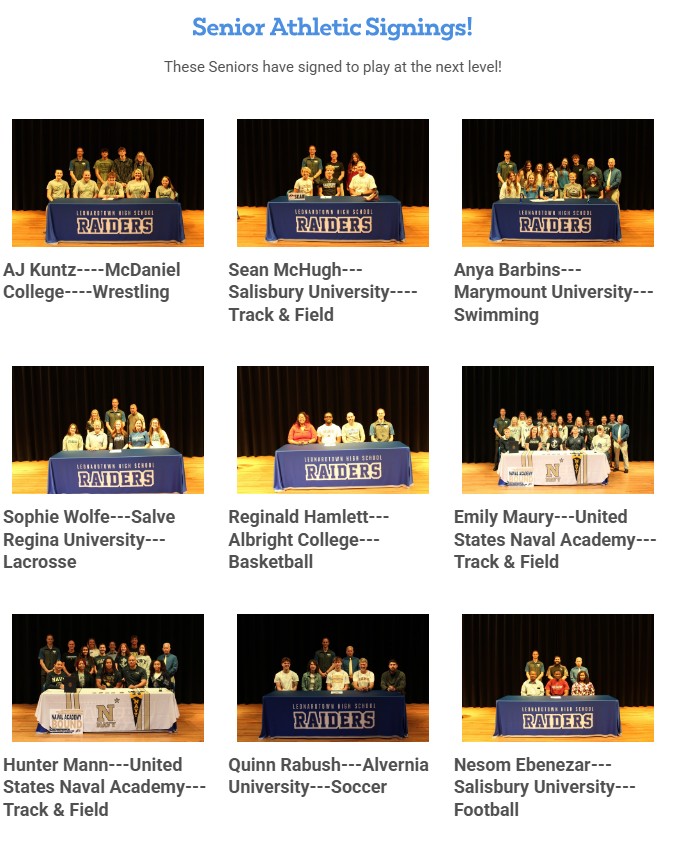

The process of becoming a Marine, a member of an elite force of armed diplomacy and swift and violent action starts off with those proud few who find the motivation to do so. These individuals come from all walks of life: a South African national whose father was in Special Forces, a talented soccer player and goalie who turned down a chance to play on a collegiate level to instead join up, a High School wrestling champ; these people come from all over the country. A thousand different backgrounds all converge at one intersection, a single life decision to put it all behind and live by discipline, by the heart and the fist, a life of passion and fury and intense motivation. That is the goal. That is the dream. The first step along this road that begin with motivation, starts with the Poolie. A Poolie is a rat, a bit of scum with motivation behind him. The poolie is less than a recruit. They are less than an unsuspecting punk kid who just signed his contract and has no idea what awaits him at boot camp. A poolie will work with their recruiters and train up; awaiting the day they can become something more. On that day they do get to boot camp, the Poolies become the recruits.

(Photo Courtesy of togetherweserved.com)

Enlisted Marines start boot camp at one of two places, either a wet sandy hellhole outside San Diego, or a swampy hellhole full of mosquitos and vicious sand fleas in the swampy low lands of South Carolina. This entrance in to boot camp is what begins the process of making marines. Boot camp is a twelve week training program that turns the average Joe citizen into a warrior. Parris Island, the more famous of the marine training programs begins the training process at infancy. The best way to make a warrior is to discard the old person, and have a better one born from the body of the first. In an effort to take away all the seventeen plus years of propaganda (or lack thereof) that teaches such pride and comfort to an average American, the drill instructors take all identity away from the recruits. A recruit crawls as he must, is taught how to walk once again (marching order), and how to dress himself (uniform dressage) and how to interact with the world (mostly fight and break things). The marine is retaught their entire life, in the hope that they will stop thinking for themselves and start thinking for the corps. At the end of this process, a marine is made. A ceremony is held. Families come out to support their loved ones. Ten days later, that pride fades away. A Marine is a fearsome individual, but a Marine without anything else is useless to the corps. A Marine requires more training.

At boot camp, a marine learns the basics to fighting: handling a rifle, obeying orders and organizing in basic combat order, but this is only the beginning. Camp Lejeune hosts Marine Combat training. Depending on the specific career paths of the marine, this training process may vary in length, but by the end, each Marine is well versed in combat effectiveness, advanced combat order, tactics and cross-training on multiple weapon systems. From here, the chaotic and troubling nature of military life carries a junior enlisted warrior (JEW) into their Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) School.

At MOS school, the marines begin to understand that there is a lot less glamour to the job. In the summer of 2013, one of the hottest on record at the training depot at Twenty-nine Palms, California, the training life of the junior marines became disappointingly stagnated. Three different crops of reservists, who are paid on a different level than full-time marines, pushed normal marine MOS trainees in the Communications program back by months, into a purgatorial existence in the hellish heat of the summer desert. It is by now that the life-decision ought to be greatly considered. The experience of boot camp, in the eyes of many gung-ho recruits, is often tamer and clearly more political than the view given in films like Full Metal Jacket. For the masochistic among the Marine warrior faith, boot camp is of little challenge to a strong body and sound mind; however, the experience found in further training is a psychological assault on all the senses. It is the worst torture, to find oneself so stagnated. For the strongest, what could be more painful than inaction itself? “They promised girls, money, pride, brotherhood,” said one Lance Corporal Blake Niles “If we were promised heaven, then why are we in hell?”

It is here, in this place of desperation and confinement that a Marine is most closely shown the sufferings of the caged beast, the sword that fears it has rusted shut in its scabbard, the brilliant prodigious mind that wastes away on remediated study. Months in the hot dessert, with few companions but those others afflicted by boredom, shows the strongest downside to the warrior life. “Some days you are the hammer and some days you are the anvil,” an anonymous warrior once admitted. Not every day does one lead the bayonet charge, or marches in dress blues and full colors to the playing of Reveille. Most days one simply waits.

(Photo Courtesy of www.marinecorpstimes.com)

The warrior ethos of the Corps shows its ugly side rather quickly. By the time all the training is passed, junior enlisted Marines are sent to their duty station, and it is here that the boredom continues, but also here where they learn that they are POGs (pronounced pogues). A POG is, in its simple use, a Person Other than Grunt, or in other words, a Marine who is not actually specialized for specific combat purposes. In broader use, a pogue is an ironic term, an insult not afar from a four-letter expletive. A pogue can be a marine who doesn’t do physical training (PT) well, or a private who fails to clean his room and make his bed well enough before inspection. A pogue is a low life- form to the warrior elite of the Marine Corps. It is an insult thrown around liberally and reminds the large part of the corps that they are, in fact, not fighters, not warriors. Only the infantrymen, the fighters, the ones that see the chaos of battle hold themselves above the insult. These are hard men; fearsome fighters that are more in tune with their animal nature.

A combat radio operator specialist is not a pogue. To clarify, any specialty that can be deployed into harm’s way is not a pogue, but one could not convince a senior enlisted Marine of this. It is a dog-eat-dog world in the corps, and the devil dogs like to bit and put themselves up as the alpha-dogs, even at the cost of putting another dog down a level. It is here that such great disappointment comes into the mix. It is difficult to move up in the world. That was the lamentation of one Lance Corporal James Morgan who referred to the “terminal lance,” or “senior lance”. The “terminal lance” is the Lance Corporal (sometimes referred to by lower ranking marines as Lance Criminal) who struggles to rank up beyond this pay grade. The ranking up slows down, now more than ever, and the titles held by rank become jokes to all those around. The terminal lance is, in the words of the marine himself, is for “infantry corporals who probably haven’t done that much or “senior lances” which is a joke in itself. I laugh when I hear a dumb grunt call himself a senior lance”. In full honesty stagnation can so easily occur. It doesn’t matter if one wishes to become more specialized, receive better training and cross training with other specialties. Senior Enlisted Marines (Sergeants, and the like) provide much of the training and assistance after MOS school. The problem is that no one wants to be a pogue. No one wants to bother with the newer Marines, at either the risk of having to deal with people unnecessarily, or in the worst way possible, be seen as a pogue. It is much like a popularity contest of the worst sort. One demands to be on the top of that social ladder that exists for the most elite (aka least pogish) of the Corps.

When stagnation occurs, and the pace slows, the brilliant façade of careful militaristic discipline and order erodes. The Marines are part of the government after all. There is no less chance of the effects of bureaucracy as with any other part of the government, and when that stagnation persists, the illusion of the personal, the passionate and brotherly bonds of warriors, becomes another outlet for making paperwork of everything. In a particular example, it is rare to get leave requests approved within a month. On record for many Marines, leave requests for Thanksgiving holiday were either approved of after having been sent in months ahead of time and then later denied because of a month-long readiness exercise, or leave that was so foolishly submitted only a month in advance was flat-out denied. Leave requests for Christmas away from Camp Pendleton barely got accepted in time to book a flight a day and a half before Christmas itself. Efficiency is an odd and illusive concept. The Marines, the military at large is efficient at training its members, setting up combat operations, deploying around the globe, handling specialized tasks, carrying out the brave tasks, but the Marines are not efficient to other regards. The Marines don’t do bureaucracy.

It is, through this training, and this entrance into a fraternity like no other, into this subculture of the modest yet prideful, the disciplined yet chaotic life, that military life is like no other day in the life of an average citizen. To be a part of the warrior tribe, is to, within a six month training period, become baptized and born anew. In the eyes of those who witness the transformation, the new warriors come forth from the crucible with a new stride, taller, broader, stronger, heartier individuals. There is a place of respect and admiration to this dedication. There is some unspoken quality, some Thumos, to the few and proud of the Marines. It is with one eye, that a witness sees the downfalls of sanity and order and the faltering of the images seen in the movies, and with the other eye that one notices the honor and pride that flows into this life style. It is, at once, so rational to piece apart this order of living, and at the other end so beyond rationalization.

Maybe that is the mistake, some missed point in the training process, that the crucible of discipline and struggle can create a new person, but it cannot take away the old rationalization, and it certainly cannot take away the rational mind of the outside viewer; but that is beyond the point of the Marines. That is beyond the point of the warrior ethos. There is no rational rationale. There is no reasoning that applies to the normal mind, for a life form so adapted to an existence that so few can actually fully understand, should not be lightly trifled with. To bounce between pride in one’s place, and disappointment in every shortcoming of the call, is to question that existence, and commit the cardinal sin of asking for a purpose. What is the purpose? That is the question asked on every side of the isle; the anti-war liberals, the skeptical conservative crowd, the confused moderates, all those outside the true military life will ask “what is the purpose?” There is both no purpose, and every sense of purpose. Lance Corporal James Morgan, offered along some sobering words of advice from a senior Marine the day he took station at Camp Pendleton, “The corps is unforgiving of weakness. If you show weakness, prepare for some pain. We are proud to be United States marines. No one can take our title. But it came with mental torment, personal purgatories, physical pain, and heartbreak. I can’t tell you how many friends lost their fiancées, wives, girlfriends of several years because they sacrificed everything to serve amongst the best.” To become the warrior is to risk more than what is reasonable, to sacrifice everything, and to ask why, especially after losing it all, would only serve to break that spirit, and invite inexorable fear when the warrior brotherhood demands only vigilance and professionalism.

It is by this way that the life of the Marine and the Military man finds existence. They serve with diligence, more so out of their own interest than a necessarily justifiable reason. The call is to find one’s own reason. The purpose is to find the purpose. To step forward without considering this; to decide to enter service to one’s country without a reason why, is a grave mistake, for there is far more to be understood of the Marines, of the Military, than what answers one can find in the civilian world. Maybe, just maybe, the only way to fully understand is through action, through imitation, through becoming that which one wishes to understand. The only way to grasp the life of the military man is to become a part of it. For everything else, and for every rationale besides, they all might so gravely miss the point.