Just Another Day in the U.S.

January 8, 2016

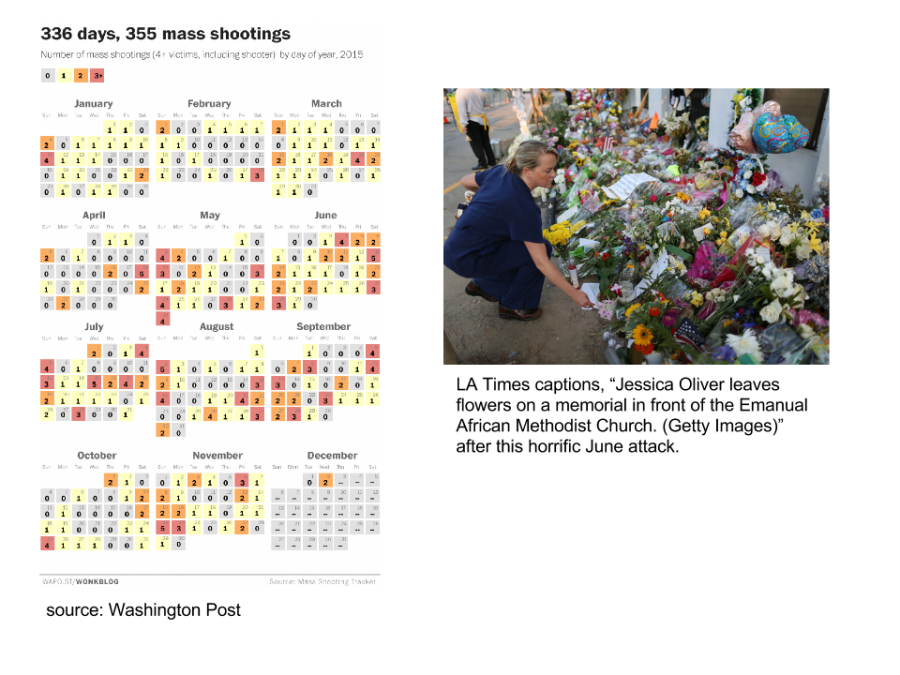

The stark reality of BBC’s opening to the coverage of the San Bernardino shooting seems to say it all: “Another day of gunfire, panic, and fear.” The attack, carried out at Inland Regional Center in California and leaving 14 dead, 21 wounded, came only days after a gunman walked into a Planned Parenthood in Colorado Springs and started firing, killing another three innocent victims. These were prefaced by an assault carried out by a 26-year old “hate-filled” individual who left ten people, including himself, dead on an Oregon community college campus. The story is all too common in the world today; so much so that after a week of coverage, many of these shootings fade into the background of public memory, only to rush back for comparison when the next erupts. The scary truth is the knowledge that at the current tracking rate, there’s a mass shooting for over every day of the year in 2015. The Guardian reports that there have been at least 355 shootings in the United States this year alone, meaning that there’s statistically enough for one a day, plus. According to shootingtracker.com, a website that’s pretty self-explanatory in itself and serves as a unique, accredited resource for news outlets, 47 states have been touched by a mass shooting and 200 cities nationwide. This figure has already surpassed the yearly total for 2014, and made a significant jump from 2013’s final count. November alone saw over 30 mass shootings, with only eight days out of thirty in which there were none. An analysis from Harvard School of Public Health and Northeastern University conducted last year concluded that between 1982 and 2011, mass shootings occurred every 200 days on average. Between 2011 and 2014, that figure skyrocketed to a median of every 64 days. The patterns don’t lie, and the coverage in the news brings the issue to a head, leaving people straining to find a reason and a way to stop this rising violence. But, is the violence really on the rise? Or, is it a major misconstrue of data?

Before coming to any conclusion, the definition of such a broad term ought to be specified. Although, there isn’t much of an official consensus on such. Generally, of course, the term refers to an event that involves multiple victims of gun violence. A 2005 FBI crime classification report identifies a mass murderer as an individual who kills four or more people in a single incident (excluding themselves), and most often in a single location. However, not everyone believes that that working definition is an accurate one. Criminologist Grant Duwe, PhD, director of research and evaluation at the Minnesota Department of Corrections, has analyzed over 1,300 mass shootings and mass murders since 1900. He’s adamant on the observing of the distinction between “mass shootings” and “mass public shootings,” or those that we generally think of in the scope of the phrase, like Sandy Hook and Aurora. In his mind, “‘mass shooting’ is too imprecise, because it could include ones that occur in the home. And most mass murders- including those committed with guns- take place in a residential setting.” By Duwe’s definition, then, public mass shootings are those that occur “in the absence of other criminal activity, like robberies, drug deals, or gang ‘turf wars,’ in which a gun was used to kill four or more victims in a public location within a 24-hour period.”

Furthermore, the criminologist alleges that from the patterns he’s studied, it may seem like mass shootings are “astronomically high” due to the dip in the mid-90s and early 2000s. Before the violent and appalling 1966 University of Texas shooting, he noted, there had been 24 mass public shootings; in the 50 years since, there have been about 135. “More specifically, the mass public shooting rate increased from the mid-1960s through the mid-1990s… Following a dip in the rate from the mid-90s through the mid-20000s, it has increased over the last decade and returned to levels that we observed during the 1980s and the early 1990s.” Trends have also been recorded in the assailants of these crimes over the years, and Everytown for Gun Safety, a nonprofit organization that petitions for gun control, came to its own conclusions on the subject. The group found that it’s only in 11% of cases that gunmen received a signed mental illness confirmations from medical, educational, or legal authorities, and that over 60% of attackers weren’t prohibited from possessing guns for prior felons or other reasons- ergo, two consensuses to factors that the public often associated to driving mass shootings. (However, they still determined that the likelihood of a mass shooting was less likely in states that require background checks for all handgun sales than in states that do not- even less of a chance in shootings by people who were prohibited by law from possessing a firearms.) Unique to the San Bernardino shooting was the fact that there was more than one assailant in the attack, and the suspects were able to flee the scene. The New York Times reports that only two of 160 active shooters from 2000 to 2013 were undertaken by more than one gunman, the FBI released in a 2014 report, while just 25 of those escaped the scene after the violence without being arrested, killed, or committing suicide. Again, this recognition only fueled the speculation for the reasons behind mass shootings: in this case, the fear that it’s radicalized terrorism becoming bolder and closer to home.

Unfortunately, the real reasons for these attacks is just as muddled as their disputed rise or fall in frequency, and are subject to political and social manipulation for the advantage of a particular viewpoint. Pop-theorists are prone to argue that crimes seem to trend whenever they tap into a larger social debate, embodying evidence for their particular causes. As such, the debate over mass shootings channels calls for a reconsideration of America’s gun control and the acknowledgement/treatment of mental illness. A constant strife for conservatives and liberals of the country, the right to bear arms and who that is extended to is at the forefront of politics in today’s world- and rightly so, as Americans are reported to own more guns per capita than any other people in any country on earth. Global group Small Arms Survey’s 2007 data showed that there were at least 89 guns for every 100 people in America- men, women, and children included. In another Harvard School of Public Health study on firearms, researchers found that across both high-income nations and states, more guns equate with more death; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention detailed that over 33,000 people passed at the barrel of a gun in 2013, with about 11,000 of these standing as homicides. Proponents of the Second Amendment counter with the argument that it’s not the guns that kill people, but the people using them. Despite this, Harvard Researchers conclude that “while many mass shooters had mental-health problems, there is no reason to believe that there has been an increase in mental illness rates in the last several years that could help to explain the rise in mass shootings.”

With no real way of knowing whether mass shootings are legitimately on the rise, nor any definite conclusion to what is driving them, is there any hope to finding a solution? Well, debatable. In a Forbes report on the issue, they highlighted a three-step proposition to what could help to curb their frequency. One that appeases both sides of the aisle is a better screening process for risk factors. Psychiatrists concede that it’s difficult to forecast potentials, but that there are typically red flags that can/could have been identified with comprehensive screenings and resulted in early interventions. Take, for example, troubled student Elliot Rodgers, who went on a rampage at U.C.-Santa Barbara. Questioned by police in 2013 after attacking an individual, Elliot was let go without any significant note to change, and followed the same when checking in with him three weeks before the crimes he committed. “Police might have done more to find out about access to firearms, just given the family’s concern about Rodger’s emotional state,” muses Duke professor Jeffrey Swanson in an interview with the Washington Post last year. “There’s no reason that police responding to people in a crisis couldn’t routinely address gun risk- talk about it, try to remove guns in various ways- instead of focusing on trying to predict when exactly somebody is going to be violent.” Some also attribute the heightened coverage of these shootings to the universalizing of terms like “mass shooting” and “active shooter” in civilian and news reports, “making them feel more in-the-moment,” according to Art Market, PhD, a professor at the University of Texas, Austin. Thus, there’s a call to stop “glorifying” the shooters in the media. Typically, mass shooters feel “marginalized by society” and have personality disorders- as such, some may act as copycat killers, revelling in the mass media attention that comes with committing such a horrible act. Instead, those who support this method call for isolating and withholding attention with the chance that it may lessen the appeal of mass shootings. “Treating mass killings as a kind of epidemic,” reports Forbes, “or contagion largely frees us from having to understand the particular causes of each act. Instead, we can focus on disrupting the spread.” Arguably most radical to the United States is the aspect of stricter gun laws.

Although not everyone agrees with the proposals, the evidence has been seen to change the state of the situation in other countries who have tightened their own. Australia stands as one of the most successful examples, enacting its strict gun control laws after a mass shooting killed 35 people in 1996. As of 2013, they hadn’t suffered a mass shooting since. Within this tighter legislation, according to Forbes, the country repurchased 600,000 shotguns and rifles, nixed private sales of firearms, and dramatically raised the bar for those looking to purchase a gun. The land down under isn’t alone, either: Germany, Finland, Italy, France, U.K., and Japan have also laid down regulations that make it harder to gain access to firearms. That’s not to say that gun homicides and suicides don’t still occur, but as Newsweek reports, “the overall rates are substantially higher in the United States than in these competitor nations.” This legislation may have gone over as a success in these nations, but would it work in America? In an op-ed on the topic, Australia’s Prime Minister declared, “Millions of law-abiding Americans truly believe that it is safer to own a gun, based on the chilling logic that because there are so many guns in circulation, one’s own weapon is needed for self-protection. To put it another way, the situation is so far gone there can be no turning back.”

While lobbyist can campaign day in and out for the Second Amendment and politicians can propose bills to restrict the measures and stipulation of public arms sales, the fact is that Americans are truly divided, taking one side or taking bits of each. Until we can come to a compromise on the subject, an answer- be it one of those already mentioned or something else entirely- will continue to evade us. What’s not in question, however, is the fact that a solution is growing increasingly requisite. “At some point, we as a country will have to reckon with the fact that this type of mass violence does not happen in other advanced countries,” President Obama addressed to the nation after the Charleston shooting in June. “It doesn’t happen in other places with this kind of frequency. And it is in our power to do something about it.” Half a year later, and the plea still stands. So when will it be answered?